Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

Moose Jaw's Urban Legend

There are tunnels below the streets of Moose Jaw. When anti-Chinese hysteria was strong, Chinese immigrants huddled in them. When Prohibition reigned, bootleggers smuggled booze through them. Or so they say.

Its eight o’clock on a weekday evening, and the restaurant is nearly empty. Two men in baseball caps glance my way, then return to drinking their coffee and saying little. They have the hard, honest look of prairie farmers. Men you can trust. A younger man is seated in the smoking section with two children. The blonde waitress takes my order, then refills the children’s plates from a nearly depleted buffet. Her hand trails across the young man’s shoulder as she passes.

It’s a place without pretensions, the kind of place that provides hearty meals at reasonable prices. My sandwich is a monumental affair and the bill comes to just $4.50, including coffee. When I go to pay, the cashier invites me to come back for breakfast in the morning. They’re open at six, and the special of bacon, eggs, and toast is just $1.99.

The people of Moose Jaw are children of the prairies. They believe in the virtue of hard work and in giving honest value for a dollar. Prairie people have always lived that way.

That’s how they’ve survived. And that’s why the tunnels are so troubling.

The Tunnels of Moose Jaw, a smartly packaged tourist attraction, has drawn tens of thousands of visitors during the past year. “Our purpose is not just to entertain, but to inform and enlighten as well,” says the tour guide. “We don’t pretend to know everything that went on. We just want to help you imagine a bit.” She doesn’t mention that the tunnels we’re about to see are not authentic. Or that much of the history is unsubstantiated. And few visitors will ever know another Moose Jaw secret—that many residents believe the genuine tunnels still remain undiscovered somewhere beneath the city streets.

Bruce Fairman runs a small computer store near the south end of Main Street. “There are tunnels,” he says, smiling. He nods in the direction of the Tunnels of Moose Jaw office, confident that I know what he means. The tunnels have all been dug within the past year.

Ron Walter, a Moose Jaw Times-Herald reporter, says, “If we were in the United States, these [simulated] tunnels would have been built years ago.” He adds, “It’s easy to be skeptical. My gut feeling is the [genuine] tunnels do exist.”

Sign up for any of our newsletters and be eligible to win one of many book prizes available.

Walter’s conviction that the legends are true is based on more than just a vague feeling in his gut. Remnants of what appear to be passageways and secret chambers have been found adjoining the cellars of more than one old downtown building. No one knows for certain who built them, or why.

However, the rumours have been circulating for generations. According to one story, the tunnels were started by Chinese railway workers about 1908, after several members of their group were attacked and killed at the CPR yards. The Chinese moved underground and lived there for years. Later, during Prohibition, bootleggers took over the network of passages. Some stories even claim that Al Capone was a frequent visitor to the city, going about his secret business under the streets of Moose Jaw.

Walter believes all that’s needed as proof of the stories is for just one member of the Chinese community to step forward and confirm them. But it may be too late for that. Seventy-six-year-old Key Wong has lived and worked in Moose Jaw since 1939.

“Honest, I don’t know much about that stuff,” he says. “About twenty years ago when some of the old-timers still lived, maybe they can tell you.” Wong suggested I contact Moon Mullin, a member of the white community. “Moon, he’s the oldest one. Maybe he knows. He was young at that lime. I think there’s some truth.”

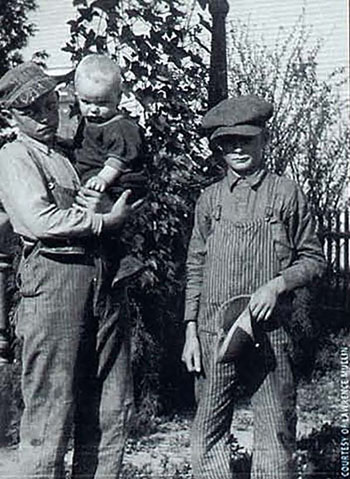

Moon Mullin claims to be one of the few surviving tunnel crawlers, if such a thing ever existed.

Some folks in town, people who should know, swear that he’s making the whole thing up. But, for his part, Mullin isn’t changing a story that reaches eighty years into his past.

You came out of the Moose Jaw station, turned left on River Street and you could have been in New Orleans. … Everything in Moose Jaw was wide open. By night the streets were really filled with men roaming around, and the traffic dawn to the whore houses at the other end of the street was something to see.

The city’s prostitutes took care of business on Manitoba Street, directly across from the CPR station. One block north on River Street, gambling and booze were king. View Street, another block north, was the boundary line that separated vice from respectability. The city gains elevation as you move north, and the term “North Hill Resident” was coined to describe the more prudish citizens who never strayed south of View Street. A careful listener can still hear the expression used in Moose Jaw today.

Born in rural Saskatchewan, on December 29, 1910, Lawrence Mullin got his nickname soon after the family moved to Moose Jaw. It was 1919, and the city was already famous for its high-rolling lifestyle.

Located at the intersection of the Soo line front Chicago and the CPR line running east and west, Moose Jaw was one of the most exciting cities in Canada at the time. In Red Lights on the Prairies, James Gray quotes a journalist who visited there just after the First World War:

I interviewed Mullin at his home on the North Hill, a long way in time and distance from the haunts of his youth. “Down there on River Street, us boys were reigning supreme,” he says. “They were all good to us.”

“Dad, he liked to play poker and he gambled. He was involved in this. Anyway these men were bringing booze in from down east on the railroad. They had this tunnel across from the CPR station … and they said to Dad, ‘Them little Chinese tunnels are so small that only they can wiggle through there with certain things. That’d be good connections for communicating if only we just had somebody that could travel through them.’ Dad says, ‘Oh, my boy can do that easy.’”

Just eleven years old, Moon was the first of five boys recruited as tunnel crawlers. He recalls hanging out at a newspaper stand on River Street. The notorious police chief Walter Johnson would ride up on his Itorse and buy a paper. “‘Storm coming tonight,’ he’d say.

“As soon as Chief Johnson was gone, I’d run over to 51 River Street and downstairs. Rap twice on the door. A Chinaman would open the door. I’d go through there and down more stairs. There would be a whole room full of men playing poker. I’d say to Jack, the guy in there, ‘Storm tonight,’ and everything would disappear!” Moon would crawl through a series of tunnels, passing the message several more times, before going back up to the Street, and home. He’d earn ten or twenty-five cents for his work.

“There is a man that nobody understood,” Mullin says of Chief Johnson. “They persecute him now, and they’re all wrong. He’s one of the nicest men that I’ve ever met. I understand now perfectly what he was going through. He was riding the fence like Sweden did during the war. And you can’t misjudge a man for that. He couldn’t work one side and not the other side. It was a way to keep communicating—with us boys through the underground, and the outside world on both sides. And of course us kids were friendly with them all.

“I never met Al Capone. Whether my mind is fading or not, I don’t know, but I think I know he was there,” Mullin says. “I knew Diamond Jim Brady, his henchman, real well.

“I can remember it vividly, just like it was yesterday, when I met him. He was about five foot ten. I’d say. Wide in the shoulders. He wore a gray suit, and he had the coat open partly in the front and I could see the butt of a gun under his arm. And he got eyes on him just like a reptile. He’d just almost paralyze you when he looked at you. He never blinked.

“He’d tell you, ‘Now look, there’s no such a thing except a good boy. I don’t want nothing to do with bad ones. I don’t believe in this crookedness [bootlegging]. This here is a way of life that we’re doing here, and it’s different, but we’re forced into this position. We’re not doing this because we like it, but we’ve got to make a living and this is the only way we can do it. But the day will come, and I’m going to tell you straight out—it’ll be as free as a bird, all over.’

“And he’s right. It is! So them men were a little more far-sighted than them that were trying to knock them down.”

After leaving the North Hill, I stop by to see Bruce Fairman again. The author of half a dozen self-published historical works, Fairman knows his local history. “I think they’ve tried to make fact from legend,” he says. He refers me to Leith Knight, a popular historical columnist at the local paper.

Knight’s views on the tunnels are well documented. In a 1991 interview with the Regina Leader Post she said, “As far as I’m concerned it all started with a couple of reporters in a beer parlour about 20 years ago. The idea was to drum up some local interest. Someone said, ‘You know, Al Capone could have come up over the Soo Line and hung out in Moose Jaw.’ So they decided to go along with it. As far as I know, that’s how it started.”

She mentions a 1986 study by Moose Jaw’s Business Improvement District (BID). “The downtown business people commissioned a study, and the tunnels and Al Capone stories just didn’t materialize,” Knight says.

But not everyone agrees with Knight. A 1986 story in the Moose Jaw Times-Herald tells about discoveries a BID investigator made while searching downtown basements. “He estimated finding clear physical proof of tunnels or passages in eight or 10 buildings in that area,” the article states. It goes on to say that the investigator also discovered archival references to a Regina lawsuit involving Al Capone.

The introduction to the BID report of the study includes the comment, “We have concluded that there is enough truth in the stories to warrant further investigation. In order to definitely prove or disprove the rumours we feel that some excavations should be done properly by professionals or semi-professionals.”

BID investigators interviewed Leith Knight. She mentions hearing rumours about tunnels connecting two houses, owned by one Sam Tadman, “who was involved in the illegal sale of liquor with the Bronfman Brothers’ Realty World.”

Unlike Capone, the Bronfmans weren’t criminals. But they owned a number of hotels in Saskatchewan and Manitoba, and temperance was ruining their business. Rather than perish, the Bronfman Brothers look advantage of the unique opportunities offered by Prohibition. They did so well that by 1928 they were able to purchase a failing Seagrams distillery for $1.5 million. Before winding up its affairs more than seventy years later, they had built the company into a Canadian icon and parlayed its value to U.S. $8 billion.

Canadian prohibition was based on the 1878 Canada Temperance Act, which gave provincial governments control of all retail liquor sales within their borders. Saskatchewan, the first province to take advantage of the act, closed down all its bars in 1915. A year later they closed all retail liquor stores. Ontario, Manitoba, Alberta, and B.C. soon followed suit. It was the Bronfmans good fortune that Quebec remained wet.

Although retail liquor sales fell under provincial jurisdiction, the federal government had retained sole control of the interprovincial liquor trade. Acting quickly, Sam Bronfman opened a mail-order liquor business in a Montreal storefront and began supplying whisky to customers all across Canada. The approach worked wonderfully until 1918, when the federal government outlawed interprovincial liquor shipments. Undeterred, the Bronfman Brothers moved on to the next obvious legal loophole: Under Saskatchewan law, druggists couid legally import and sell liquor for medicinal purposes. Harry Bronfman, who ran the Balmoral Hotel in Yorkton, procured a wholesale druggists licence, and the brothers were soon major distributors of whisky to drugstores all over the province.

By the time Canadian restrictions were removed in 1920, American prohibition was already in place. With their warehouse full of liquor in Yorkton, the Bronfmans were ideally placed to begin exporting to markets south of the border. And under Canadian law it was all strictly legal, as long as provincial taxes were duly paid on liquor shipped to the States.

The tunnel legends have been fuelled over the years by recurring street cave-ins, which often reveal mysterious underground cavities. Some of the tunnellike openings are explained away as old utility corridors. But others aren’t so easily dismissed. The collapse of a manhole in 1985 exposed what the BID report called a large “brick-lined, bell-shaped area” under the street. City workers didn’t think the opening was part of the sewer system, and speculated that it may have been a cistern. According to a witness, interviewed for the study, the opening had been used for more than storing water. “A woman who lived in the Elk Block in the 1940s remembers seeing people, mostly Chinese, coming up out of a hole off the alley between River and Main when there was a fire in a boarding house on Manitoba.

Similar anecdotal evidence exists in abundance. The report tells of a local doctor who “remembers being called to a Chinese business on River Street West and being taken through a maze of passageways to where his patient was. He felt he went through at least two buildings and perhaps went under the alley.”

Remnants of what appear to be passageways and secret chambers have been found adjoining the cellars of more than one old downtown building. No one knows for certain who built them, or why.

The Exchange Café, owned by Key Wong’s family, is frequently associated with the legends. Wong is perfectly willing to talk about the old days, but denies any knowledge of the tunnels. “We didn’t have a tunnel at all,” he says. “They try to promote that. Why does Moose Jaw have it? Why not Regina … Why not Winnipeg?”

Wong’s father and uncle purchased the café in 1931, and he joined them when he came to Canada in 1939. He was fifteen years old. “River Street was really booming.” says Wong. “Day and night. Lots of people. My dad told me they served alcohol in a teapot. Everybody was serving. Might as well do it himself. People demand, you supply and make some money. That was under Chief Johnson. Whether Capone was there or not, I have no idea.”

The café is gone now, replaced by a bootleg theme motel that stands on the original site across from the CPR station. One popular anecdote recounts a time when Chief Johnson escorted a group of prostitutes to the station and ordered them to leave town. Later that day the women were sighted by a number of witnesses—filing out of the Exchange Café. It’s not clear whether they returned on the first train, or never left town in the first place. But those telling the story all say that to avoid being seen leaving the station, the women made their way to the Exchange Café through a tunnel running under Manitoba Street.

I ask Wong about allegations that the tunnels were used to hide illegal immigrants. The BID study mentions a 1962 court case against a Chinese family who were accused of bringing in illegal immigrants. The accused were said to have had connections with the Exchange Café.

“I never heard much about illegal [immigrants] at that lime,” Wong says. “Those people came from the same area as my dad. I forgot to ask if he paid the $400 head tax. Most of the cooks came from the same area. We had sixty staff.”

Maurice Libby, another local writer, has thoroughly researched the city’s early history for his new book Moose Jaw: A Popular History. Written with coauthor John Larsen, it is scheduled for publication in July by Couteau Books. Libby doubts that Moose Jaw’s early Chinese immigrants had any reason to go underground.

“The first I heard of that was on the Tunnel Tour” he says. “It wasn’t in the original legends I heard as a kid. Moose Jaw had one of the biggest populations of Chinese on the prairies. The reason is that it was a friendly place for Chinese. There wasn’t really a Chinatown. There was no Chinese ghetto.”

He describes the tunnel stories as being like smoke. “When you try to contain them and see what substance they have, they just curl through your fingers and disappear.”

But Libby is no scoffer. “I’ve seen what looked like the entrance to a tunnel under the Exchange Café. Years and years ago, we had the use of the building for a drop-in centre and discovered a doorway in the basement with a collapsed space behind it.”

His research suggests that the tunnels originate from the early part of the twentieth century, a time when the downtown core had suffered a great deal of damage by fire. Hoping to prevent further serious fires, the city passed a bylaw requiring that all heating plants in the downtown core be maintained by a professional engineer. Libby speculates that doorways were created between many basements, making it possible for the engineer to move from one building to the next without coming up on the Street.

Canadians like to think of themselves as a tolerant society, but racism was officially sanctioned in this country during the early years. Chinese immigrants were exploited for their labour in railroad construction, forestry, canning, and other industries where workers were hard to find.

The Chinese were hated and mistreated, and, as white workers became more available, laws were put in place to keep them out. In 1885, a $50 head tax was placed on Chinese immigrants, and it rose by increments until 1904 when it peaked at $500.

The reality of racism and the damage it’s done are perhaps the most important lessons taught by the Tunnels of Moose Jaw tours. But no real evidence exists to support the stories of persecuted Chinese living in the underground tunnels, or that Chinese even built them. Some may argue that the lessons are significant enough to justify a certain carelessness with truth and accuracy. Others, however, are offended by the approach.

Grant and Sally Chow are third-generation owners of a 109-year-old heritage building on the corner of Main and River Streets, just a few doors from the Tunnels of Moose Jaw offices. Grant teaches engineering at the college, and Sally runs a specialty cafe on the main floor of the building.

“They never really talked to anyone in the Chinese community here,” says Sally. “They’re making money out of our ancestors—what they’ve gone through.”

Grant says his grandfather and great-grandfather both paid the head tax, and he doesn’t believe the Chinese ever lived in tunnels. “My dad indicated he’s not aware of it.” He acknowledges, however, that a lot of information has probably been lost.

“We do have tunnels in our basement, though,” says Sally, smiling. Grant adds that the building to the south of him also has tunnels. He says the Tunnels of Moose Jaw company offered each of them one dollar a year for twenty years to run tours through their basements. The company excavated its own tunnels after Grant and his neighbour turned the offer down.

It’s growing dark by the time Grant leads me downstairs. We pick our way through old grocery store fixtures and other remnants of bygone days to the north side of the building. There he points out an old wooden door set into the concrete wall. Casually swinging it open, Grant shines a light into the tunnel. I guess that it’s about ten metres long. Both ends are blocked by rock and mortar. I step through the door, and realize l’m standing in one of the original Moose Jaw tunnels. Bits of glass, perhaps smashed whisky bottles, litter the floor. It’s easy to believe this was once the lair of bootleggers.

Tunnels clearly exist, but the mystery remains. A few old-timers tell their stories, while others scoff. In the meantime, the legends have spread across the nation.

The second passageway is directly east of the first one. It seems a little longer, but the ends are sealed up in the same way. Light leaks through a manhole cover in the ceiling, and Grant points out sections of railroad track put in place to keep the River Street sidewalk overhead where it belongs.

Tunnels clearly exist, but the mystery remains. A few oldtimers tell their stories, while others scoff. In the meantime, the legends have spread across the nation. Tourists are pouring into Moose Jaw, the city with the strange name and the colourful history.

Maurice Libby says the city has seen hard times and the tunnel tours have given it hope for the future. “Young people don’t take it for granted that they’ll have to leave to be successful. People are coming back to the city. The legend of the tunnels is contributing to its recovery.”

While waiting to meet Libby at a Main Street restaurant one afternoon, I asked a college student what she thought of the tunnels. “There has to be something to it,” she said. “There’s too much evidence out there for it not to be true.” She added that she’d taken the tunnel tours with her class, and been very impressed. I asked if she was a history student. “Oh no,” she said. “I’m a marketing major.”

The morning after my discovery of the real tunnels in Grant and Sally Chow’s basement, I leave my luxury suite at the Temple Garden Spa for the last lime. The hotel, which includes a natural geothermal pool on one of the upper floors, is part of an urban renewal plan conceived by the BID. It’s become a popular stopping place for tourists who come to visit the tunnels.

Before leaving town I walk down to the old red-light district for one last look around. On my way back I notice that a new movie, Urban Legends, is playing at the old Capitol Theatre. Nothing else has really changed. Men and women, carrying the burdens of a lifetime, move through the streets as they’ve always done. They’re the children of the prairies, believing in the virtue of hard work and giving sound value for a dollar. That’s how they’ve always lived. And that’s how they’ll survive.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!