Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

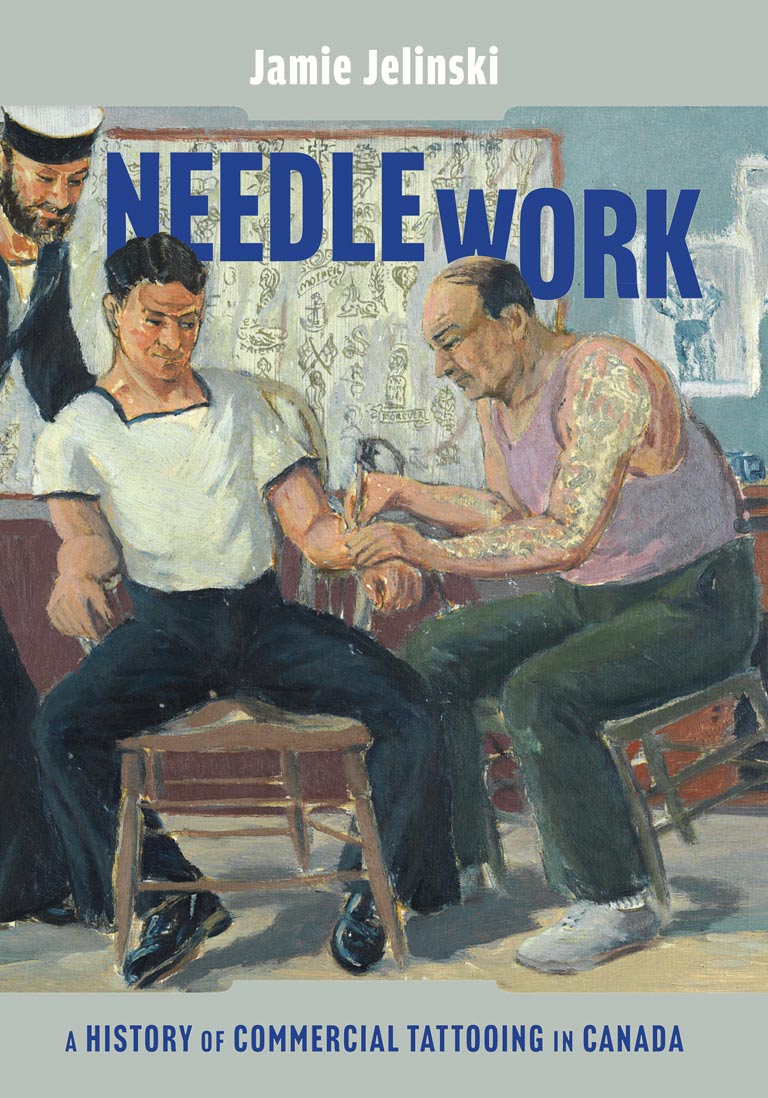

Needle Work

Needle Work: A History of Commercial Tattooing in Canada

by Jamie Jelinski

McGill-Queen’s University Press

424 pages, $75

While researching a book on Jennie Churchill, mother of former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, I came across an intriguing assertion. A previous (and not always reliable) biographer mentioned that Jennie had a tattoo of a snake on her wrist. I knew that the beautiful, exuberant Jennie loved to shock — it was part of her charm. But I doubted that a woman who swanned around Britain’s most aristocratic circles in the late nineteenth century would venture into the grimy, crowded streets of East London to have a design traced on her bare skin. During this period, and into the mid-twentieth century, tattoos were working-class acquisitions, popular among sailors and labourers and frequently associated with criminals.

Failing to find a second source regarding Jennie’s tattoo, or even to spot the snake on one of the many glamorous photos of her, I omitted it from my account. But now I’m having second thoughts. In Needle Work, a book by visual-culture scholar Jamie Jelinski, I learned that the Western infatuation with “Japonisme” during Jennie’s lifetime had led members of the British royal family to acquire tattoos, as did the son of American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Three of Queen Victoria’s sons flaunted tats. Jennie Churchill, who was the premier fashion influencer of her day, might well have embraced the trend.

In Needle Work, Jelinski focuses almost exclusively on tattoo practitioners who are Canadian and non-Indigenous. Until recently, tattoo art was regarded as marginal, while tattooists in the settler society (almost all of them white and male) were often too itinerant and too illiterate to leave many written records.

While the book claims to be a work of history, it is constructed on an analytical rather than chronological frame, and the extraordinary amount of detail threatens to overwhelm a reader. Jelinski is determined to omit no tattooist who has left a trace — a newspaper advertisement, even a business card — in the archives. His five chapters, he suggests, “are best understood … in ongoing conversation with one another.” I guess this excuses some repetition, since conversations are like that.

A lengthy introduction sets out the author’s themes. He intends to explore the working conditions of tattooists — “the techniques used by commercial tattooists to advance their individual careers and quality of work as entrepreneurial image makers” — during the twentieth century. Jelinski explains that in earlier years few tattooists had the skills and confidence to tattoo freehand. Instead, they relied on “flash”: pre-made, standardized tattoo designs that were applied to a customer’s skin as stencils and then traced over with a tattoo machine. Hearts, scrolls, women, flowers, animals, flags — the kinds of images that were also popular on picture postcards and product packaging — were standard flash items and were often traded between practitioners. Tattoo equipment evolved over the century, particularly after the introduction of electric machines.

Initially, authorities in Canadian cities regarded tattooing as a dubious procedure, liable to spread infection and practised by suspicious characters. The book’s first chapter covers attempts by police, politicians, and public-health officials to regulate the activity. The second chapter expands this thesis with an exhaustive look at one particular tattooist, “Sailor Joe” Simmons, a truly fishy character who, over his lifetime, was pursued by both Canadian and American police forces for various petty crimes. Sailor Joe left a satisfying trail of court records and newspaper exposes that Jelinski has mined extensively.

There is a change of pace in the next chapter, which looks at tattooing activity in Vancouver and Victoria, coastal cities where the practice flourished among bored sailors on shore leave. This enables Jelinski to document the slow improvement of tattooists’ workspaces, from rooming houses, to penny arcades, to tattoo shops, barber shops, and, eventually, an art gallery.

After exploring tattooing activity in Halifax, Jelinski takes the story up to the 1970s and 1980s, during which commercial tattooing began to enter the art world. Toronto painter Aba Bayefsky was a significant bridge between the worlds of tattooing and art. He taught at the Ontario College of Art (now OCAD University) and created a series of works in the 1970s and 1980s that depicted tattooed bodies, both of his friends and of men he met in Japan. By that time, several tattoo artists had moved on from flash images to imaginative customized designs. One of Bayefsky’s favourite subjects was William Freeman, a tattooist who chose to have his whole body covered in designs, including his face, head, and hands.

By the 1990s, tattoos were creeping into the mainstream. In 1993, Montreal’s upscale Queen Elizabeth Hotel hosted an “International Tattoo Expo” that was attended by three thousand people. This event is featured in Jelinski’s epilogue, although the author takes the story no further. He has not covered the explosive growth of the industry since then or explained how tatting moved so fast from the back streets to Main Street. Today, tattoo shops seem to be as ubiquitous as hair salons. Every self-respecting hipster seems to have at least one, and Pinterest offers its followers “120 Best Taylor Swift tattoo ideas.”

Jelinski has given us a deeply respectful study of the tattooing industry. While Needle Work is not a particularly accessible book, copious fascinating illustrations demonstrate the evolution of the activity and its practitioners.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement